Book type: Sociology

Summary: In David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, published October 2013, Malcolm Gladwell continues his tradition of compiling individual stories of success and failure and weaving them together to illustrate broader theories than what they could’ve told us on their own. He begins with the age-old tale of David and Goliath, a battle between a small shepherd boy and a warrior whose very name would become a synonym for giant. He walks the reader through the story step by step and then tells us that we’ve misunderstood the point of the story for centuries. The meaning of the story isn’t that David beat all odds and actually won against Goliath, it’s that the odds were actually on his side–he wasn’t really an underdog after all, because his tactic was one that Goliath didn’t expect. Let’s dig into some lessons that can be learned from underdogs.

Lessons:

- “Giants are not what we think they are.” One of the very first assertions Gladwell makes is that “The same qualities that appear to give [giants] strength are often the sources of great weakness. And the fact of being an underdog can change people in ways that we often fail to appreciate: it can open doors and create opportunities and educate and enlighten and make possible what might otherwise have seemed unthinkable” (6). In the case of David versus Goliath, when each side chose the fighter to represent their entire army, the Philistines–in an obvious move–chose their largest, most intimidating warrior. The Israelites, having no comparable warrior, struggled to choose a representative until David volunteered. Even then they struggled, but he insisted and they let him go. He won because he had no intention of going mano-a-mano, he was a skilled slinger, and when he threw his stone, Goliath had no chance. Goliath’s size and abilities would have been unmatchable had the battle been a conventional one, but David exploited his opponent’s weaknesses–his size, his armor, and his expectations–and he walked away with his head. (Pretty much what the Seahawks did to the Broncos during the Super Bowl tonight.)

- Advantages are sometimes disadvantages. There are two stories that deftly illustrate this principle. The first is about a Hollywood exec who was raised without all the advantages of wealth, but then having amassed great wealth himself, struggled with raising his own children to appreciate the value of a dollar. What Gladwell asserts is that wealth, like many other advantages, can cease to be an advantage at a given point and then actually become a challenge (in this case, a family’s overall happiness will increase to around the point of a family income of $75,000, then it maxes out, and at some point can make a family unhappy, 49). The second is about a woman who loved science, was very smart, and therefore decided to go to Brown University, an Ivy League school, over the less prestigious University of Maryland. The conventional thinking is that a degree from a more prestigious school is worth more than one from a regular public university. And this is sometimes true. But in the sciences, if you’re average at Brown or Harvard or MIT, you’re much less likely to get published (and therefore less likely to be impressive) than if you were brilliant at an average school (87-89). He further points out that if you’re in the bottom third at Harvard in terms of your math/science SAT scores, you’re just as likely to quit your science-related major and get some other degree as someone in the bottom third at a less prestigious school like Hartwick College, even though your SAT score was higher than the highest third at Hartwick. In other words, the bottom third at Harvard (the group you fall in) has an average score of 581. The top third average score at Hartwick is 569. So your low score at Harvard is still better than the best average score at Hartwick, but it doesn’t end up mattering. The ostensible advantage you expected to gain from going to Harvard is moot and you’ll probably end up publishing less than if you’d been the big fish in the little pond at Hartwick. For the woman who went to Brown over the University of Maryland, the outcome was that she quit her science major, her real passion, because she compared herself to several other brilliant people and fell short, even though she would’ve been brilliant at another school: “What matters, in determining the likelihood of getting a science degree, is not just how smart you are. It’s how smart you feel relative to the other people in your classroom” (84). Feeling dumb at college? Try switching to a different school before you abandon your passion.

- Disadvantages are sometimes advantages. You saw that one coming, didn’t you? Much like David opposing Goliath, several people have had disadvantages that end up propelling them to greatness and Gladwell’s book contains several examples. One specific challenge that he focuses on is dyslexia. He tells of several highly successful businesspeople and entrepreneurs who, because of their dyslexia, have had to learn in ways that are different than most of us. (One example in the book is a lawyer who grew adept at listening and memorizing speech because of his difficulty with reading.) In addition to this “compensation learning” (113), the effect of dyslexia for some children can be that they become so accustomed to “failing” that they don’t feel the social anxiety many of us would feel about being what psychologists call “disagreeable” (123). One example given is Gary Cohn, President and COO of Goldman Sachs who jumped into a cab with a Wall Street big shot and pretended he knew about options trading (when really he had no idea whatsoever) and managed to be offered a job and then had to learn everything he needed to know before he started his job the following week. Most of us would never dream of doing something so bold as what Cohn did; we’d fear being found out or being shunned and embarrassed. But for Cohn, who was accustomed to failure, it was an opportunity to get himself out there. And it worked. We may not believe his method was right just as many didn’t believe it was right for Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights protestors to allow children–or use them, depending on your viewpoint–to attend their rallies and be attacked by police dogs in order to bring awareness to their cause, but Gladwell points out that “…We need to remember that our definition of what is right is, as often as not, simply the way that people in positions of privilege close the door on those on the outside” (190). Hearkening back to a book I covered last year, Nine Lives, the best way is not always through, sometimes it’s around. Sometimes you can’t play by the rules because the rules are not made to include you, so you have to be creative and get it done your own way.

- “When people in authority want the rest of us to behave, it matters–first and foremost–how they behave” (207). Gladwell gives a few different examples to drive this point home, the most heartbreaking of them being the force used by the British Army in responding to unrest in Northern Ireland in the 1960s and ’70s that resulted in thirty years of warfare and appalling bloodshed. The failure of the British Army was that the method they followed was one of showing their might instead of understanding how the people, particularly in Belfast, saw them, namely as invaders who were there not to keep peace, but rather to protect and defend the Protestants, who were like them. Had the Army behaved differently, perhaps the Troubles wouldn’t have happened as they did. Another example, and one that we would do well to follow in our own lives, particularly as parents (of children, or if you’re me, of puppies) is of a teacher and a classroom gone haywire. Gladwell describes a video of a teacher whose class of youngsters has gone off the rails: kids with their backs turned to the teacher, a little girl doing cartwheels, etc. and he points out that many of us would be quick to say the kids are misbehaving or just general troublemakers. But really the fault lies with the teacher in this case because if you see the whole video, you see her focus on one child and become unaware of the needs of all the other students. As Gladwell puts it:

We often think of authority as a response to disobedience: a child acts up, so a teacher cracks down. Stella’s classroom, however, suggests something quite different: disobedience can also be a response to authority. If the teacher doesn’t do her job properly, then the child will become disobedient (206).

Remember that next time your kid won’t stop whining or your dog chews the legs of your couch. It’s most likely not them, it’s you.

A final review/recommendation:

As you may know already if you’ve followed my blog for a while, I’m a big Malcolm Gladwell fan (read my lessons from Outliers and Blink if you haven’t already). He consistently does a great job at gathering compelling stories and including data from studies that corroborate his theories (although if you also read the lessons from Proofiness, then you’ll know you should always be wary of numbers). Overall, David and Goliath wasn’t my favorite Gladwell book–Outliers is probably still my top choice, though I have yet to read The Tipping Point–but it was an interesting read and a fast one, so if you’ve read his other books and liked them, or if you’ve read my blogs on his books and liked them, I would recommend checking it out. And if you don’t feel like reading it, you can listen to it on YouTube for free (although admittedly I didn’t listen to much of it, seeing as I’d already finished the book in paper form).

Thanks for reading, congrats to the Seahawks, and please take note that my birthday is in 15 days and I might just post a wish list on here, considering when I mentioned in a previous post that a neighbor may have stolen my orange watering can, a brand new one from Amazon arrived at my door a few days later (thanks to my aunt and not a stalker, I discovered later, much to my relief), so make sure you check back to see what I want before that special day sneaks up on you.

From an underdog–no, just a misfit,

CCRider

Photo credits:

Book cover: http://static4.businessinsider.com/image/525d891e6bb3f785521e39b2-1200-2000/gladwell_david%20and%20goliath.jpg

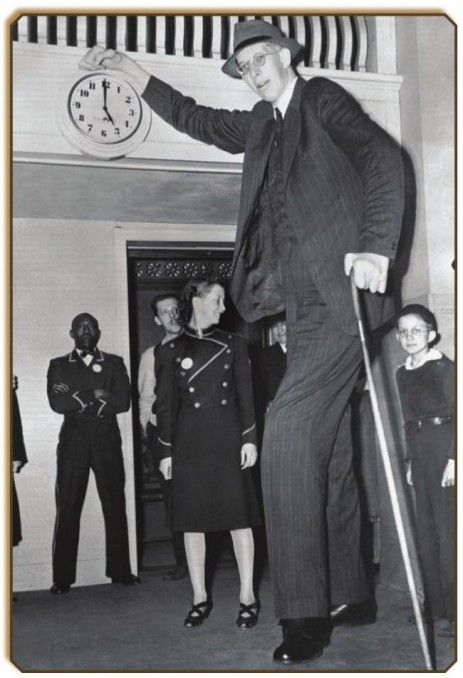

The real Goliath: http://designyoutrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Robert-Wadlow-1-650×951.jpg