Book type: History

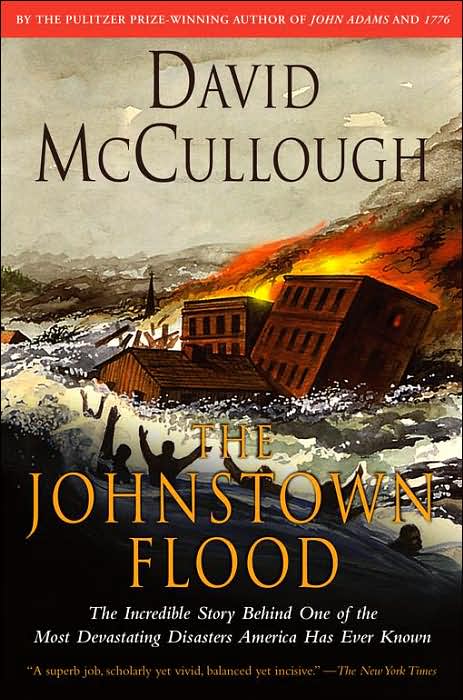

Summary: Before he wrote 1776 and before he won the Pulitzer Prize for Truman or for John Adams (which HBO famously made into a mini series), David McCullough wrote The Johnstown Flood: The Incredible Story Behind One of the Most Devastating Disasters America Has Ever Known. In fact, he wrote The Johnstown Flood before he wrote anything else. This very first book of his, originally published in 1968, tells the story of what happened to a handful of communities in the mountains of Pennsylvania–communities who lived in the shadow of a large lake held back by an earthen dam, a dam which burst just after Memorial Day in 1889. What is surprising to learn about the Johnstown flood, is that it really wasn’t a huge surprise at all. It had broken several times before the final blow amid constant rain in the spring of 1889, and it even became “something of a local joke,” something that everyone kept waiting for and then never happened; until it did (66). Here are some lessons we can all take away from the tragedy that devastated a Pennsylvania valley and that gripped a nation over a century ago.

Lessons:

- If you’re going to go about changing the natural order of things, you’d better know what you’re doing. The South Fork dam was a manmade construction, and ultimately it failed because the men who owned the property it was on failed to heed warnings and make necessary repairs that could have saved thousands of lives. The water that broke loose from the dam “charged into the valley at a velocity and depth comparable to that of the Niagara River as it reaches Niagara Falls. Or to put it another way, the bursting of the South Fork dam was about like turning Niagara Falls into the valley for thirty-six minutes” (102) and by the time it was over–an extremely brief amount of time at that–over two thousand people would be dead, and the bodies of many would never be recovered. After the flood, many writers “took up the old line that if God had meant for there to be such a thing as dams, He would have built them himself. The point, of course, was not that dams, or any of man’s efforts to alter or improve the world about him, were mistakes in themselves. The point was that if man, for any reason, drastically alters the natural order, setting in motion whole series of chain reactions, then he had better know what he is doing” (262). Frankly, much of the time, man has no conception of what the possible outcomes may be. Countless times throughout history humans have made alterations to an ecosystem just to find that their brilliant idea wasn’t so smart after all. Whether it’s introducing new species to an area or decimating a species to help with something else, too often we make things worse by trying to make things in nature better. Be careful how you play with the Earth, my friends.

- Don’t assume that you’re safe in the hands of others. The South Fork dam was owned by a group of businessmen from Pittsburgh who liked to visit their manmade lake for fishing and “roughing it” in comfy cottages. These businessmen were almost all millionaires of the steel industry, and the people who lived in the valley all year round made the mistake of thinking that the rich people who owned the dam wouldn’t let it fall into disrepair. After all, why would they want to run the risk of the dam breaking on them too? Unfortunately, these men weren’t engineers and they never consulted experts to weigh in on the safety level of the dam. Because the people in the valley assumed the rich guys knew what they were doing, they didn’t press them about potential safety hazards or necessary repairs, and when the dam finally broke for good, many of them didn’t even know what hit them. Literally. The floodwaters tore down trees, telegraph poles, houses, barns, and anything else along the path down the mountain, such that when the flood was nearly upon residents in the various cities, they couldn’t even see the water. All they saw was the debris. Many people heard the devastation coming but didn’t see it was a flood. (Of course several knew the rains were probably the cause, or may have known that the dam had broken, but all they saw was the wreckage straight at them.)

This stone bridge caught much of the debris (human as well as timber) when the flood made its way down the mountain. The same night as the flood, the wreckage caught fire and several people were trapped inside. Eventually, it would take a large amount of dynamite to break it all loose.

- Don’t jump to conclusions. So often we’re tempted to provide our own theories of how a tragedy has come to pass without having all the facts, and the days after the Johnstown flood definitely illustrated this principle. Some argued that it was the start of the Final Judgment and everyone else should prepare for what was to come, while others blamed the rich guys for not maintaining the dam properly, and still others said that clearly it was God showing his displeasure with the sins of Johnstown, a judgment in line with the Old Testament story of Sodom and Gomorrah.

It was a line of reasoning which many people were quick to accept, for at least it made some sense of the disaster. But it was a line of reasoning which met with much amusement in Johnstown, where, as anyone knew who knew his way about could readily see, Lizzie Thompson’s house [a brothel] and several rival establishments on Green Hill had not only survived the disaster, but were going stronger than ever before. “If punishment was God’s purpose,” said one survivor, “He sure had bad aim” (252-253).

- Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than to be good. Several people survived the disaster out of pure luck (or providence, depending on your point of view), when seemingly everyone else around them died. As a train car full of people fled for the hills when the water was almost upon them, the baggage master J.W. Grove, hopped on top of a train engine nearby instead of following everyone else to the hill. “Every other loose engine in East Conemaugh was dumped over, driven into the hillside, or swept off with the flood, except the one he picked” (124). Additionally, all of Johnstown’s three or four blind people survived the flood, while around them, “Ninety-nine whole families had been wiped out. Three hundred ninety-six children aged ten years or less had been killed. Ninety-eight children lost both parents. One hundred and twenty-four women were left widows; 198 men lost their wives” (195). There was no sense in who died and who was spared, most of it was pure dumb luck, like the family of six who survived having their house thrown on its side and impaled by an oak tree. Sometimes you can’t know what you should do in a given situation and have to hope and pray you just make it out. As one of the steel mill owners said in a speech to the community during their first church service after the flood, “‘Think how much worse it could’ve been. Give thanks for the great stone bridge that saved hundreds of lives. Give thanks that it did not come in the night. Trust in God'” (236).

The most amazing fact is that the house is still mostly in one piece, unlike almost every other house in the town.

A final review/recommendation:

McCullough’s book is a captivating look into a historical tragedy that dominated all the important newspapers of the time for several days (it was the front page story for the New York Times for five straight days) and yet one that most Americans have probably never heard of. It’s a story of death, but also of rebuilding and community, of people losing their families, but also helping to save others, and it offers several insights that are just as true for us now as they were for the residents of the cities in the shadow of the South Fork dam in 1889. For those who are history fans and for those who are not, it’s a heart-wrenching story and it’s worth checking out.

Photo credits:

Book cover: http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_hY-4lomJSGs/STd5INqgYuI/AAAAAAAAAwo/dxFdjDgggWU/s1600-h/Johnstown%2BFlood.jpg

Stone Bridge: http://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/5johnstown/5images/5img3bl.jpg

Treehouse: http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/lindariesphotoguide/johnstown%20tree%20in%20house.jpg